The Maintenance of Racial Harmony Bill: Another death-knell for democracy

Today, 4 February 2025, Parliament will debate the Maintenance of Racial Harmony Bill (”the Bill”).

This is a legislation long in the making. In his 2021 National Day Rally, then-PM Lee Hsien Loong first signalled the government’s intention to introduce the Bill. He prefaced this announcement with a long rumination on the fragile state of racial harmony in Singapore, and the global threat of polarising race relations.

The government’s characterisation of race and religious issues as security threats that require state intervention is well documented. Jothie Rajah’s seminal work Authoritarian Rule of Law: Legislation, Discourse and Legitimacy in Singapore discusses how the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (”MRHA”) of 1990 was part of efforts to repress potential challengers to its power, such as a burgeoning Catholic social justice movement, as well as entrench state authority over religious discourse.

Though thirty-five years apart, the Maintenance of Racial Harmony Bill is a direct successor to the MRHA. The key elements of the Bill are clearly drawn from the MRHA (which was significantly amended in 2019).

However, there are significant and worrying differences – the Bill still further expands the scope of state intervention into public discourse and speech by granting broad powers to the Minister of Home Affairs with little oversight to boot.

This article’s primary focus is to break down some aspects of the Bill and address the implications for civil liberties and the Rule of Law.

Overview of the Bill

The Bill has three main thrusts:

First, it introduces powers for the Minister of Home Affairs to issue Racial Content Restraining Orders. The stated purpose is to restrict acts that could cause enmity, ill will or hostility between races.

Second, the Bill provides the Minister the power to designate organisations or entities, thereby introducing obligations to report its finances or governance arrangements to the government, and to give the Minister powers to intervene in the governance of the organisation/entity.

The government’s stated purpose for these power is to reduce foreign influence in ‘race-based organisations’.

Third, the Bill consolidates and amends existing Penal Code offences relating to race and religion, while significantly increasingly penalties. A separate article will discuss these changes.

These provisions are supplemented by a range of supporting provisions in the Bill, including:

- The introduction of a Presidential Council of Racial and Religious Harmony;

- The removal of the power to seek review in the Courts of the decisions of the Minister, the Council and the President;

- The power to create regulations to facilitate the implementation of the laws. These regulations are not subject to parliamentary oversight.

The Power to issue Racial Content Restraining Orders

Under Section 8(1), the Minister of Home Affairs may issue a ‘Racial Content Restraining Order’ against a person or entity, if the Minister is satisfied that X has “committed, is committing, is likely to commit or has attempted or is attempting to commit” an “act that causes feelings of enmity, hatred, ill‑will or hostility between different races in Singapore”.

This requirement is also met if they are encouraging or instigating anyone else to do such an act.

Once that requirement is met, under Section 8(2), the Minister may make a restraining order of the following:

- To stop writing or speaking to the public or some group of persons [ss (2)(a)] ;

- To stop distributing information or material to the public, whether by placing it on the internet or some other medium, or having someone else do it on their behalf [ss (2)(b) read with ss 7];

- To remove information from being accessed by the public [ss (2)(c)];

- To stop writing for or being a part of a publication (e.g. a newspaper or online media platform) [ss (2)(d) and (e)]

This restraining order can be applied to “any specified” subject matter, topic, theme, information, material, or publication that the Minister deems fit.

The extremely broad scope created by “any specified” becomes immediately obviously when the restraining framework in the Bill is compared with the restraining order framework found in Section 9 of the older Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act.

Section 9(2) of the MRHA sets out that the restraining order could either prevent someone from speaking to or advising any religion group or institution, or to stop “any communications activity involving information or material, concerning or affecting the relations between that religious group or religious institution and the Government or any other religious group or religious institution.”

In other words, in the MRHA, Minister has to establish a rational connection between the targeted content or communication in the restraining order and the potential outcome of religious disharmony that it is seeking to prevent.

This creates at least the need for some specificity in an restraining order under the MRHA.

This same rational connection does not need to exist in the restraining orders under the new Bill. There is nothing in the law preventing the Minister from issuing broad prohibitions, so long as the s8(1) requirement is met (i.e. the Minister takes the view that X has done an act or is potentially doing an act that affects race relations).

For example, if X has commented on the ethnic make-up of prisoners in the Singapore Prisons, the Minister could issue a restraining order preventing X from talking about the Singapore Prisons generally (the Singapore Prisons being the “any specified” subject matter).

In contrast, if X were about to comment on the religious make-up of prisoners in the Singapore Prisons, the Minister could only issue you a restraining order to prevent you about that specific issue and not preventing X from talking about the Singapore Prisons as a whole.

Under the new Bill, you could just as easily expand the prohibition to prevent X talking about whether policing is racialised (which decides who ends up in prisons), or even the criminal justice system as a whole.

While common sense dictates that this would clearly be a disproportionate response that restricts legitimate discourse by X, nothing in the law prevents it.

Returning to Section 8(1), what are the circumstances under which the Minister would be ‘satisfied’ that someone “is likely to commit” some act resulting in racial disharmony and thereby can issue a restraining order?

Saying that X is likely to do something is an act of speculation. Whether that act of speculation is based on a reasonable amount of evidence is an entirely different question. Only the Minister has to be ‘satisfied’ – not being a criminal prosecution in a court of law, no formal rules of evidence or standard of proof govern the Minister’s satisfaction.

‘Preventing Foreign Influence on Race’

Part 4 of the Bill also prescribes the Minister with powers to take “measures against foreign influence”.

The predominant power introduced in Part 4 of the Bill is the power to designate entities if their purpose or activities include either representing or promoting any race [s 15(a)(i)] or discussing any issue relating to any race [s 15(a)(ii)].

It is not a requirement that the purposes above are the main purpose of the organisation, so long as it is one of the purposes.

Once this requirement is met, the Minister may make the designation if it is “necessary or expedient to pre-empt, prevent or reduce any foreign influence that may undermine racial harmony in Singapore” [s 15(b)].

First, the power to designate any entity so long as one of its purposes, however minor or peripheral, is to discuss any issue of race creates a catch-all. Would an organisation advocating for anti-poverty, which takes the view that the intersection between socio-economic marginality and ethnicity is important, fall within the scope? Presumably it does.

Second, the word “expedient” grants great discretion to the Minister to make the designation. Expediency means that there only needs to be a broad or loose connection between the act of designation and the intended outcome of pre-empting or reducing foreign influence. And, how pre-emptive could a measure be? Would a 5% reduction in foreign influence suffice satisfy the criterion? Would a 5% increase in likelihood of preventing foreign influence satisfy the criterion?

Given the ease with which the Minister can designate an entity under Part 4 of the new bill, it is abhorrent that this designation comes with serious consequences.

First, the designated entity has to report all foreign and all anonymous donations [s 18]. The designated entity must also to report any arrangement they have with a foreign entity (person or organisation), where the foreign entity has some kind of decision-making power in the arrangement. The Minister can determine what kinds of arrangements or relationships need to be reported and the details to provide [s 19].

Second, the designated entity would also have to disclose their governance arrangements (such as by providing a copy of its constitution to the Minister), and the identities and nationalities of people running the entity [s 20].

Third, the “responsible officers” (e.g. the President, secretary and treasurer in the case of a society) of a designated entity must be a Singaporean or PR) [s 24]. Half of the governing body must also be made up of at least 50% Singapore citizens, or in the case of a governing body with 3 or less seats, must be fully held by Singapore citizens. [s 23]

The Minister can issue a removal direction, forcing the designated entity to remove non-Singaporeans in these positions if it is necessary or expedient to pre-empt, prevent or reduce any foreign influence that may undermine racial harmony in Singapore.

Finally, the Minister can also take further measures in the form of ‘Foreign Influence Restraining Orders’. [s 27] Using these restraining orders, the Minister can prohibit the entity from receiving any foreign or anonymous donation (or to return any such donation), stop the entity from entering into any agreement with any foreigner, and prevent appointments of (or have the entity suspend) anyone from its governing body (whether Singaporean or not).

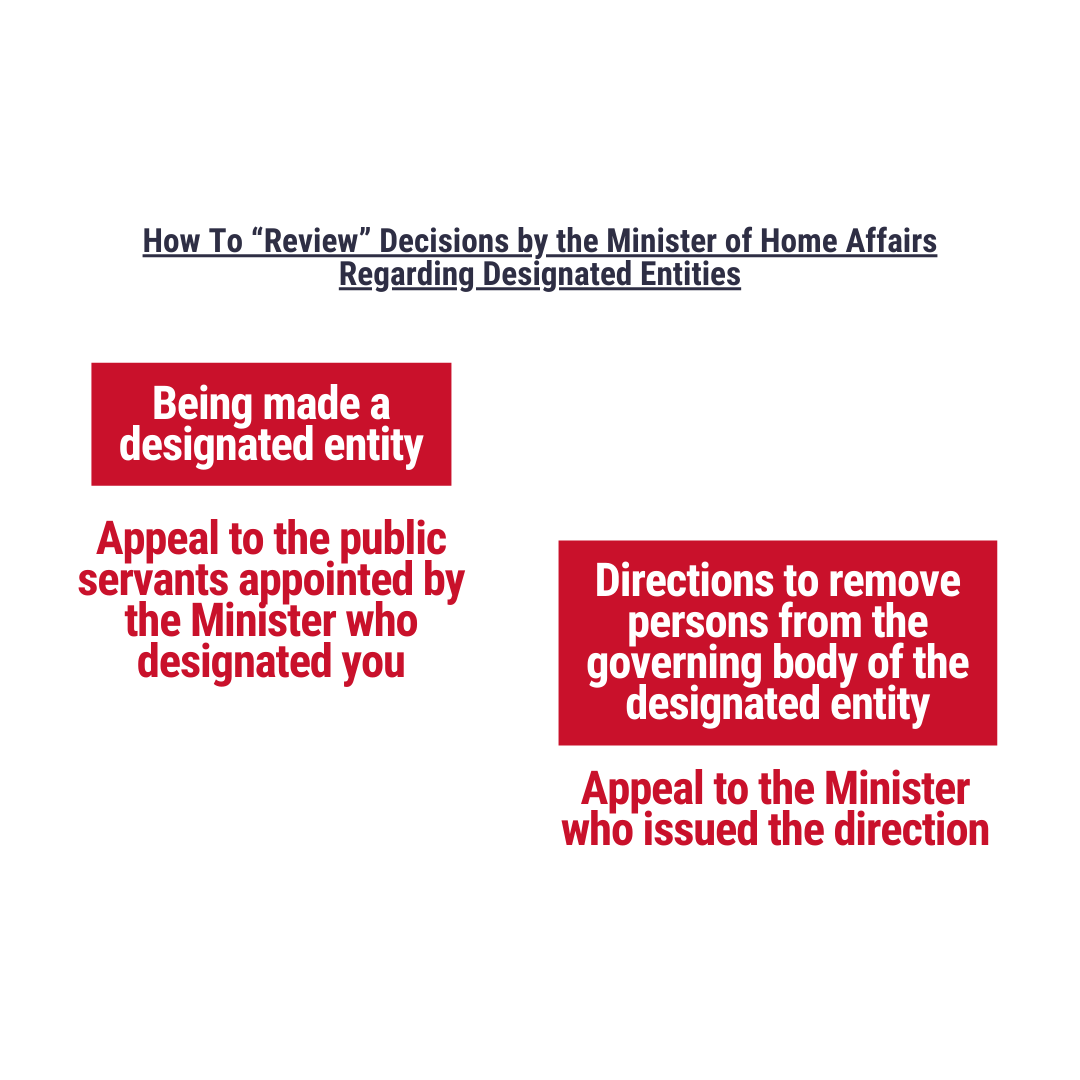

With respect to any obligations arising from being a designated entity, non-compliance may result in fines for the entity or the individual who is targeted by the Minister’s orders. The Minister’s decision to issue a removal direction, and the Minister's designation can be appealed to the Minister, but the Minister’s decision in such an appeal is final (yes, you read that right).

Non-compliance with the foreign influence restraining orders are on the other hand punishable by fine and/or a term of imprisonment.

In sum, by giving powers to intervene in the governance of organisations or other entities, Part 4 of the Bill poses serious implications for the freedom of association.

Is there sufficient oversight?

We have an expectation that the government sticks within the boundary of the laws it seeks to pass into force. If the laws are broad and all-encompassing (as above), or grant great discretion to the decision-maker, we might still think the upholding the law requires the exercise of state power to be done reasonably. This is the fundamental principle of the Rule of Law. If government action is unconstrained by law and basic reasonableness, we live in an autocracy.

When the government exercises powers beyond what is in the law books, or exercise its power unreasonably, we would seek to challenge the decision or act of the government in the Courts as a separate branch of the State. This is the check and balance to executive power, underlined by the separation of powers. If the safeguards against executive power are not independent, the Rule of Law is meaningless.

The new Bill carries an explicit ouster clause in Section 42, which reads:

All orders and decisions of the President and the Minister and recommendations of the Council made under this Act are final and are not to be called in question in any court.

It should be noted that the MRHA, passed in 1990, contains an ouster clause which is the same word-for-word. What has changed however, in the intervening 35 years, is the judicial and social attitude towards the need for check and balance of the government’s power.

As recently as 2019, the Singapore Court’s pronounced the following in the case of Nagaenthran. In that case, the Court considered whether Section 33B(4) of the Misuse of Drugs Act was a valid clause removing judicial review. At [71] and [73] of the decision:

“...the court’s power of judicial review, which is a core aspect of the judicial power and function, would not ordinarily be capable of being excluded by ordinary legislation”.

...

"in any society that prides itself in being governed by the rule of law, as our society does, must hold steadfastly to the principle that ‘[a]ll power has legal limits and the rule of law demands that courts should be able to examine the exercise of discretionary power’”.

The new Bill’s clearly and expressly worded ouster clause seeks to completely remove the jurisdiction of the Courts to review executive decisions and orders pertaining to the new Bill. It can only be surmised that the government has taken lightly basic democratic principles.

In place of judicial review, the Bill instead prescribes appeal mechanisms against restraining orders which are woefully inadequate, for the reasons below.

Under Section 33 of the Bill, any person or entity issued a restraining order may make written representations to the Presidential Council of Racial and Religious Harmony (“the Council”) within 14 days.

The Council is introduced by s 2 of the new Bill and replaces the Presidential Council of Religious Harmony from the MRHA.

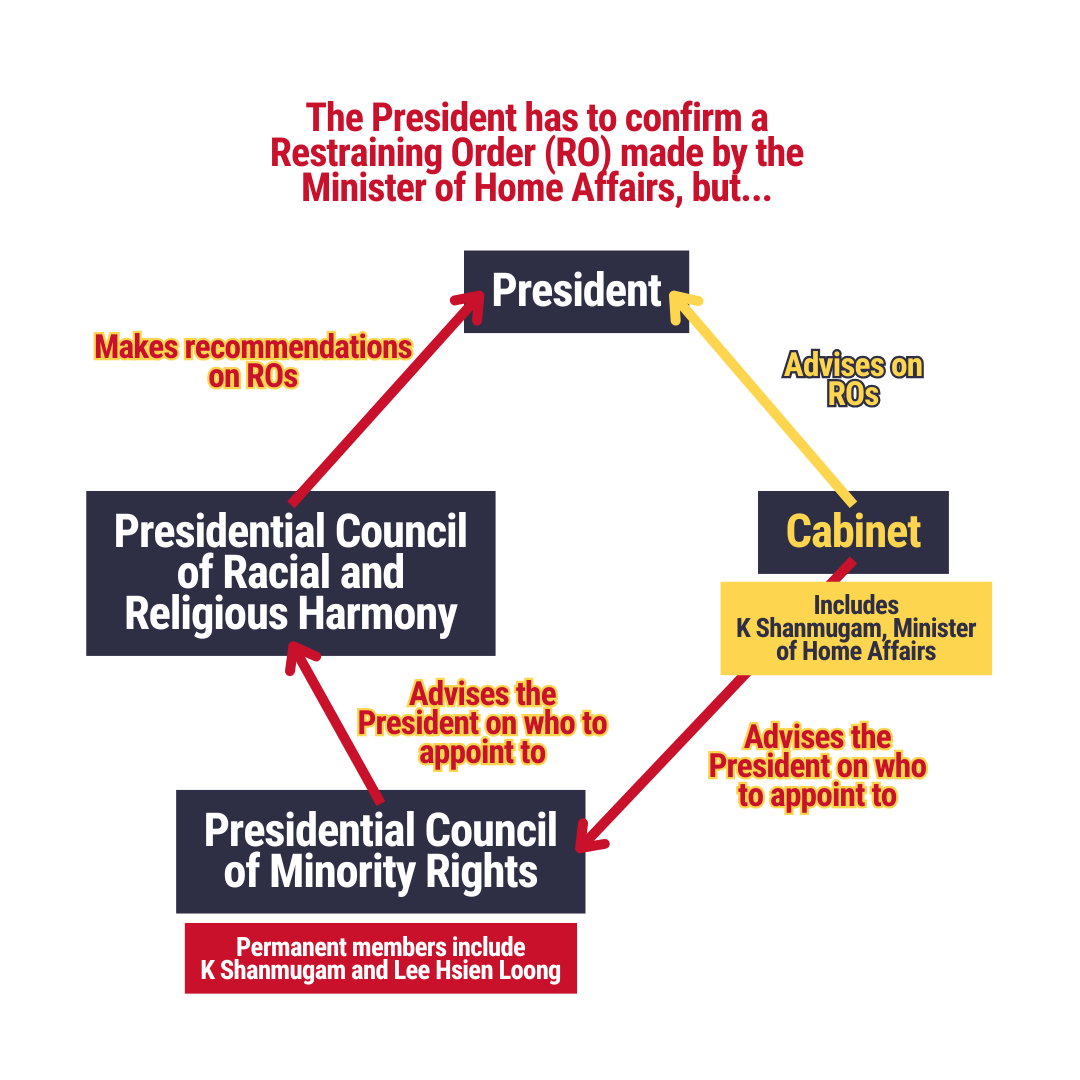

Within 44 days of the restraining order, the Council must make a recommendation to the President that a restraining order be cancelled, varied, or confirmed. Separate to the Council’s recommendation, the Cabinet must advice the President on whether to confirm the restraining order.

If the Cabinet’s advice and the Council’s recommendation are the same (the exact words are “not contrary”), the President has no discretion and has to uphold the advice/recommendation.

If the Cabinet’s advice and the Council’s recommendation differ, the President has discretion to decide whether the restraining order should be confirmed or varied or cancelled.

A number of issues arise:

First, the restraining order will be in force for up to 44 days, regardless of whether the restraining order is ultimately cancelled or confirmed by the President.

Second, if you miss your 14 day period after the order is made, you no longer get to make representations on the restraining order.

Second, it is extremely unlikely the Cabinet’s advice would differ from the Minister of Home Affairs’ decision to issue the restraining order – since the Cabinet is made up of the government including the Minister of Home Affairs.

Even if the Cabinet as a whole were minded to consider more substantively what to advice the President, there is no requirement for the Cabinet to consider the Council’s recommendations or the representations of the restrained person or entity before delivering its advice to the President, since from the reading of the legislation, these are independent processes.

Third, in considering whether to confirm the restraining order or make a different recommendation, the Council is constituted informally - rules of procedure that would ordinarily ensure fairness in legal proceedings do not apply here (or are not transparently applied). Section 33(5) states that the Council could ask to examine the person or entity issue a restraining order, but there is no automatic right to be heard. The Council’s procedures are not judicially reviewable.

This is sets a lower standard even compared to the Reviewing Tribunal under the Foreign Interference Countermeasures Act, which reviews directions issued by the Minister to stop communications or block access to content.

Fourth, the independence and expertise of the Council is questionable.

Schedule 2 of the proposed bill sets out the composition of the Council. Appointees of the Council are selected such that the Council represent various race and religions and that the Council has persons distinguished in public service or community relations. Would they be able to adequately handle the task of reviewing the restraining orders issued by the Minister? In comparison, the Reviewing Tribunal under FICA is at least chaired by a Supreme Court judge.

The independence of the Council is also in question, since members of the Council are recommended for appointment to the President by the Presidential Council of Minority Rights.

The President Council of Minority Rights is appointed by the President on the advice of the Cabinet, and its permanent (lifelong) members include senior government officials past and present, including Lee Hsien Loong and K. Shanmugam, the Minister of Home Affairs himself.

Finally, we have yet to see an instance where the President has exercised their discretion (where the Constitution allows for it) to go against the wishes of the Cabinet.

I would also add it is surprising that the powers under Part 4 are excluded from even weak review mechanism provided for the restraining orders, given the serious implications designation has for entities. For restriction orders under Part 4, an appeal may only be made to the Minister who issued the restriction. To challenge a designation Minister, the appeal is to the competent authority (the public servants appointed by the Minister to exercise the powers in this law on his behalf) and the decision in such appeals are final.

To note: Under POFMA, where the appeal against a correction direction issued by the Minister goes firstly to the Minister him/herself, we have not seen a single instance where the Minister has set aside their own decision. (In POFMA, if the appeal to the Minister fails, the Correction Direction is then challengeable in Court.)

The Minister’s Investigative Powers

Section 6 provides that the competent authority (basically, the public servants appointed by the Minister to exercise the powers under this law on his behalf) may, by written notice, require a person to answer any question or provide any document.

While this is similar to Section 108 of the Foreign Interference Countermeasures Act (”FICA”), there are also key difference.

First, the scope of s 108 is narrower since it pertains to specific purposes under FICA. Second, in 108(2)(a) of FICA, the power to require information or any document may only be exercised if the competent authority deems it “necessary”. Finally, in relation to the exercise of the powers, there is no express power in s 108 to require that passwords or access codes or information be provided to the authority.

Even someone under criminal investigation has more protection under the Criminal Procedure Code ("CPC"). The power of the Police to require the provision of other passwords or access under Section 39(2A) of the CPC applies when a police officer “has reasonable cause to suspect is or has been used in connection with, or contains or contained evidence relating to, the arrestable offence”.

The only requirement in Section 6 is that the power of investigation is being exercised for the purpose of performing any function conferred on the Minister or competent authority by the Bill (or checking compliance with existing orders or directions). In other words, there is no real requirement.

Failure to comply with a request under Section 6 of the Bill result in criminal sanctions.

Conclusion

I have sought to show that the Bill grants extensive powers to the Executive, in particular the Minister of Home Affairs.

The latest Bill follows a trend of legislating broad administrative powers to the Minister that are backed up by criminal sanctions, most notably in POFMA, FICA, and the Online Criminal Harms Act. The rapid fire introduction of such laws as if it were ordinary legislation has gradually shifted norms about the appropriate scope of the state and state intervention into free speech and expression.

It is also evident that each new law is built on the last, with the mechanisms of state intervention and intrusion further refined, and the boundaries of acceptable incursions into basic liberties stretched northwards.

This is yet another death knell for the already tattered vestiges of our democratic rights.

Credits: Elijah and Koki for graphics.